About the Parish

This information first appeared in the revised edition of the English Martyrs Parish Booklet

- Rich in history

- Nineteenth Century poverty

- Setting up the Mission

- Killed in mail train accident

- Unique location attracts growing interest

- English Martyrs Church

- Architectural style

- Martyrs’ journey from earth to heaven in mosaic

- German Mission in East London

- Demographic Change and Mounting Debt

- Cholera epidemic of 1866

- Overseas fundraising efforts

- Working for change

- Movements and Initiatives

- The League of the Cross

- The C.Y.M.S.

- English-speaking national pilgrimage

- The Guild of Our Lady of Ransom

- Catholic Seaman’s Club

- Twentieth Century Begins

- Urban renewal threatens parish school

- Martyrs’ canonisation

- War clouds gathering

- Time to celebrate 100 years

- Adapting to change

Rich in history

English Martyrs church is in a part of London of special Catholic interest. Close by is the Tower of London, which was a royal palace in pre-Reformation England. The Tower was once surrounded by religious foundations, including Holy Trinity Priory, where Trinity House stands today. The Tower Hotel is built on the site formerly occupied by St Katherine’s Hospital, which was founded by Queen Matilda, wife of King Stephen. The convent of the Poor Clares (Sorores Minores), known as “Minories”, has given its name to a busy thoroughfare, and Saint Clare’s House stands on the site of the former convent.

The most famous of these foundations, the Abbey of Our Lady of Graces in East Smithfield, founded by King Edward III, became a place of pilgrimage and a centre of Marian devotion.

With the coming of the Reformation, these places of prayer and popular devotion were quickly suppressed and the Tower became the final dwelling place of many brave men and women who died for their Faith. Among those who died here were St Thomas More and St John Fisher, both canonised on 30 June 1935. The site of the Martyrs’ Scaffold can be seen at Trinity Square, close to Tower Hill underground station.

Nineteenth Century poverty

Social conditions in England had rapidly deteriorated by the early 1800s. After the Napoleonic Wars, England’s trade monopoly ended and she was forced to compete with continental producers. The ensuing recession led to widespread distress among industrial workers. Farming communities also fared badly. The steady stream of unemployed agricultural workers into East London helped swell the growing numbers of Irish and European immigrants. Overcrowded miserable dwellings (aptly portrayed in the novels of Dickens) and the complete absence of sanitation led to the spread of disease.

The spiritual plight of poor people who lived in those unhappy times was even worse. “Drunk for a penny, dead drunk for two pence” was an invitation to seek temporary relief from appalling misery.

The beginning of English Martyrs Parish dates back to 1864, when Cardinal Wiseman authorised the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (Oblates) to set up a mission extending eastwards from London Bridge to the end of the docks, and southwards from Aldgate to the shore of the Thames. It was to be known as the Tower Hill Mission.

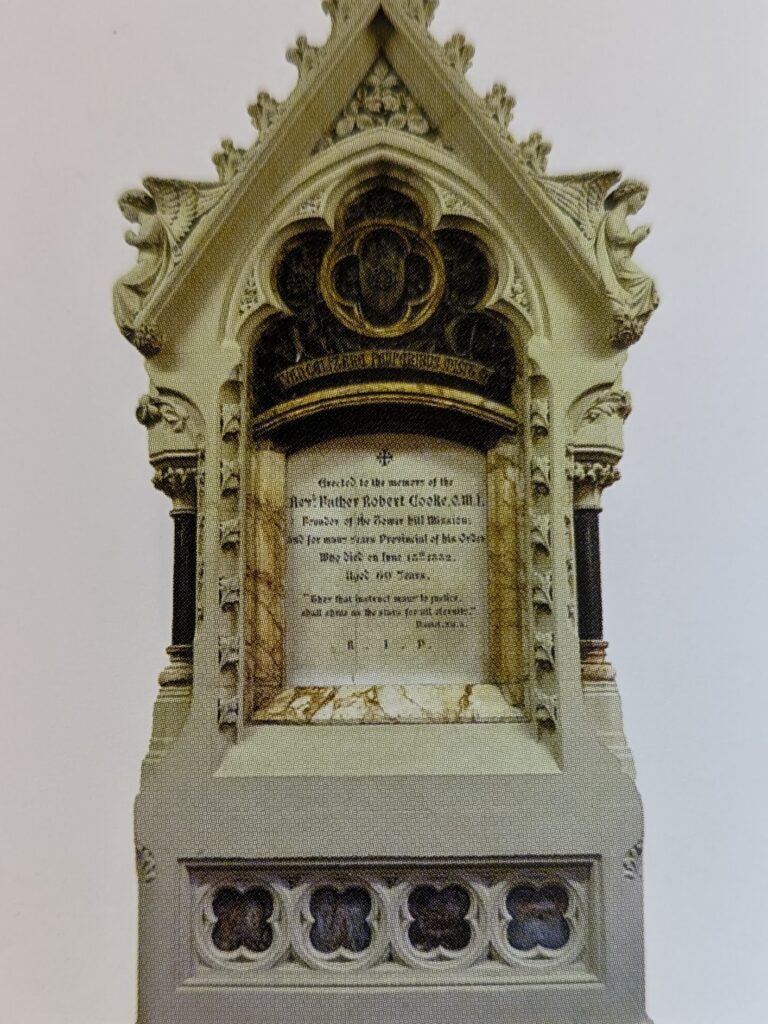

When the Oblate Founder, Eugene de Mazenod, visited Whitechapel fourteen years earlier, in 1850, and saw the depth of poverty and degradation, he urged Fr Robert Cooke (the then vicar provincial) to take the necessary steps to open a mission in London’s East End.

At his canonisation in 1995, Pope John Paul II said of Eugene de Mazenod: “He was a man of Advent… he not only looked forward to that Coming, he dedicated his whole life to preparing for it, he was one of those apostles who prepared the modern age, our age”.

Setting up the Mission

A chapel on Virginia Street, which had previously served the needs of poor Catholic refugees, had been pulled down to make way for the expansion of the docks down-river. A new church to replace it, St Mary and St Michael’s, was built about a mile away on Commercial Road. This large church could accommodate the population, estimated at 16,000, but for many of the 7,000 people living in Rosemary Lane and the alleys and courts off it, it was too far away.

For some months, Fr Cooke trudged the streets in search of a site for a church. One morning as he passed along Holborn he felt weak and went into the offices of Mr Charles Walker, a moderately wealthy partner in his family’s successful cartography business. Charles Walker, who was almost certainly known to Fr Cooke, was a remarkable person and one of the first to join the SVP when it started in London. He was a key figure in getting Catholic churches established in poorer areas of the city, and incredibly generous to Catholic causes. He was not married, and lived near Russell Square with his two brothers and four sisters, also unmarried. They maintained a very frugal lifestyle in order to give away as much as possible. When Fr Cooke told him of a plot of ground for sale at Great Prescot Street, he gave him the £1,000 required as a deposit on the site. The purchase price was £3,200. Fr Cooke rented three tenement rooms in Postern Row on Tower Hill and moved in that evening. The following morning, the feast of the Annunciation 1865, he celebrated Mass on Tower Hill, the first in more than 300 years. The news spread quickly. Next day hundreds of poor Catholics gathered under the railway arch spanning Mansell Street to hear Fr Cooke declare the Tower Hill Mission open.

Within a week, Fathers Ring and Crane joined Fr Cooke. Shortly afterwards, the last two members of the team, Brothers Malone and Woods began work on the construction of a corrugated iron building that would serve as church, parish centre and temporary school. Cardinal Manning blessed this temporary church, dedicated to the English Martyrs, on 12 December 1866.

Some time later the Oblate Community moved to 26, Prescot Street, and the founding group of four Poor Servants of the Mother of God moved into a small house in Chamber Street, Tower Hill. Among the four was their founder, Frances Taylor. Dedicated to working with the poor, they taught children by day and adults at night, and worked in the local industrial school. They continued this immensely valuable work until the arrival of the Holy Family Sisters in April 1870.

Killed in mail train accident

Fr Edward Healy OMI, who was attached to Tower Hill mission in the late 1860s, was a friend and adviser to Frances Taylor in new her religious Congregation’s foundation year. The SMG Annals record that he was “a man of rare virtue, great calmness of judgment, warm powers of sympathy… who took the warmest interest in the enterprise and, in many an hour of discouragement and difficulty, was at hand to aid and to give advice”. In September 1870, before he returned to Tower Hill from a retreat in Ireland, Frances Taylor met him at Inchicore, Dublin to discuss accepting postulants. She left Dublin for Wexford on September 15th thinking that Fr Healy had taken the morning mail boat on the previous day. At Kingsbridge Station she heard the newsboys crying: ‘Fatal accident on night mail from Holyhead’. She had a dreadful premonition, confirmed when she read the newspaper. Fr Healy had drowned when the train crashed into the River Trent at Tamworth. His travelling companion, Fr Ring was injured but managed to swim to safety. Fr Healy was just thirty-three years old.

Unique location attracts growing interest

Thanks largely to the networking skills of Fr Cooke and his ability to ‘market’ the location’s unique history, English Catholics were becoming interested in the Tower Hill project. High profile supporters included English converts, City businessmen, Irish MPs and some descendants of English and Scottish Catholics who had suffered in the Tower.

Lady Londonderry, Lady Georgiana Fullerton and Lady Lothian should be introduced into the story at this stage. They were all converts, key supporters of Tower Hill, and close friends. Lady Georgiana was also a friend of Frances Taylor. As well as supporting Frances Taylor’s community, they were tremendously helpful to English Martyrs School in its early years. Another key figure was John Young, an architect who had an office in Mark Lane and was the only Catholic on the City of London Corporation at the time. He was very involved in parish fundraising efforts, and was commissioned to design the first permanent school.

Fr Cooke left the mission in the care of Fr William Ring, a man of profound faith and a gifted organiser. His first concern was to provide the community with a proper school. Using all his networking skills, he put together a group of influential supporters and, in 1870, Princess Marguerite of Orleans laid the school foundation stone in the presence of the Duke of Norfolk, Lord Denbigh, the Earl of Granard, and the Marchioness of Londonderry and many others. The four-storey building was completed and opened to receive pupils in 1872. Pending the construction of a permanent church, the top floor of this building served as the church. Brother Malone’s corrugated iron building became a parish hall.

English Martyrs Church

Although in debt to the tune of £2,500, Fr Ring instructed Peter Paul Pugin to draw up plans for a new church, and work on this project began towards the end of 1872. During the construction phase the new church’s proximity to the Tower attracted increasing interest from prominent English Catholics. Many saw in it the fulfilment of Cardinal Newman’s vision of a Second Spring. During his famous sermon on the restoration of the Catholic Hierarchy, at Oscott College in 1850, Newman spoke of the “second temple of glory rising from the ruins of the old, nourished by the blood of our martyrs three centuries ago and since”. Tower Hill mission honoured the English martyrs on 22 June 1876, when, in the presence of a large congregation of their fellow Catholics, Cardinal Manning dedicated the new church to their memory.

Architectural style

The church was built in neo-perpendicular Gothic style. It presents a fine facade to a street that is otherwise inconspicuous. A delicate design in buff brick and Portland stone carries an elegant tracery from the porch to the deep relief of the rose window that surmounts the double oak-door entrance.

To the left, a small tower culminates in a slender pinnacle pointing heavenwards to proclaim that this is a place of worship. The church is perhaps too broad for its overall length. The architect was constrained by the site, which was too shallow for his purpose. He was faced with the problem of building a church capable of serving a parish of some six thousand people on a site that was quite inadequate.

Accordingly, he designed a church, the exterior of which would present pleasing proportion to the aesthetic sense. However, the interior departs from full harmony with classical expectation. The gallery is mainly utilitarian and obtrudes stolidly on the main lines of the interior design. It is a heavy structure in well-cut stone, supported on massive granite columns. The fine foliage carvings of the capitals cleverly relieve the weight of this gallery. These granite columns are carried through from the balcony to the lofty arches that support the well-lighted clerestory. The clerestory culminates in a graceful ribbed stone ceiling that carries the full length of nave and chancel. Another pleasing feature of the balcony is the proportionate groined ceiling that gives an inward cloister effect to the spacious gallery.

The complete absence of timber in the interior design is a rare un-Pugin-like feature. The incomplete transept is carried from a lofty slender arch on the west side to the Lady Chapel on the east side. The Lady Chapel is the Shrine of Our Lady of Graces.

Besides the exquisite foliage capitals on the pillars, a wealth of stone sculpture adorns the church; no cornice and no pedestal has been left without its floral or angelic decoration, but it’s the excellent stone statuary around the sanctuary that merits most attention. Beautifully cut statues of Our Lady Help of Christians and St Joseph, set in domed niches on elaborately carved pedestals, can be seen on either side of the sanctuary arch. The Holy Spirit altar on the south of the transept is particularly rich in its execution.

Martyrs’ journey from earth to heaven in mosaic

The reredos, in Portland stone, depicts in three panels the Descent of the Holy Spirit. Our Lady and St Peter are shown in the centre panel. The side panels depict the other apostles in groups of five. It is reasonable to suppose that Mr Boulton of Cheltenham did this work, since Pugin & Pugin often used his renowned skills. We do know with certainty that he executed the beautiful statue of Our Lady in the Shrine of our Lady of Graces.

The original plan was to have a shrine to the English Martyrs on the south wall of the transept, but it was decided instead to embellish the high altar as a shrine with significant representations. This was done in 1930, when group statuary presenting no fewer than twelve of the martyrs was erected on either side. The high altar is simple in design of stone and marble with the monograms of the Passion and the Oblate escutcheon superimposed. It is tastefully relieved with colourful gradine in mosaic and the use of gold leaf to emblazon the tracery on the frontal. The wrought-iron grille that forms a back-drop to the high altar carries the armorial bearings of the following martyrs: John Fisher, Thomas More, Adrian Fortesque, John Houghton, Oliver Plunkett, Margaret Pole, Richard Reynolds, Ralph Sherwin, John Stone and Richard Whiting. A magnificent stained glass window occupies the full wall space behind the altar. Designed by William Early, and made by his firm in Dublin, it was erected in 1930 as the main feature of the shrine. In its vertical and traverse lights, surmounted with the rose and additional pointed arch of the window, it has some thirty-two English Martyrs grouped around the Crucified Saviour, the King of Martyrs.

The Sacred Heart altar on the gospel side is simple in design and its reredos has a mystic presentation of King David with St Margaret Mary. The alabaster altar rails, although not in use nowadays, serve to confine the speciality of the reserved sanctuary and complete its overall decoration.

Shrine of Our Lady of Graces

The Shrine of Our Lady of Graces commemorates the Abbey of Our Lady of Graces built by King Edward III and sits in the Lady Chapel, east of the transept.

German Mission in East London

By the 1850s a sizeable German Catholic population resided in the Tower area of east London. They had come to find work in the huge sugar factory and the docks, and to escape persecution. Using a disused concert hall as their church, St Boniface’s, a succession of German priests were responsible for their pastoral care. The Oblates took on this misson following a request by Archbishop Manning through his friend, Father Robert Cooke. Father James Bach, the first German Oblate to come, was replaced by Father Victor Fick on July 7, 1872. There was some friction between the Irish and German communities concerning the use of the church, but Fr Cooke and the Archbishop did much to resolve the issue. Fate intervened, however, when, on 30 April 1873, St Boniface’s Church collapsed just after hundreds of parishioners had left evening devotions. Only the large crucifix from the roof remained standing in the ruins.

The Oblates withdrew from this commitment in 1876 because it was not possible to build a new ‘St Boniface’s’ and ‘English Martyrs’ at the same time. The small territorial district assigned to St Boniface’s was given to Tower Hill mission, which became responsible for the non-German, mostly Irish, Catholics living there.

Demographic Change and Mounting Debt

In the space of eleven years Tower Hill Mission had grown from a tenement slum into a well-established parish with its new school, new church and even a parish hall. The presbytery at 26, Prescot Street was barely habitable, but a debt of £27,000 meant that work on a new one would have to wait. The annual income was not enough to pay the £1,000 annual interest on the debt.

Help arrived from an unexpected source. At the suggestion of Cardinal Manning, Pope Pius IX asked the Abbot General of the Carthusians of Chartreux to help. The Carthusian Monastery of Chartreux, mindful of the martyrdom of forty Carthusian monks on Tower Hill and hearing that English Martyrs was in financial difficulties, donated a sum of money to help. This was enough to have 26, Prescot Street rebuilt and fitted out in 1881.

Further challenges lay ahead, however, as the population declined sharply. By the early 1880s the Catholic population of the district assigned to Tower Hill dropped catastrophically from 7,000 to 2,000, due mainly to massive slum clearance schemes. At the same time, an influx of Jewish people began pushing the non-Jewish population eastward. In 1882, it was agreed with Westminster Archdiocese to extend the Tower Hill district a few streets eastward, taking some additional territory from St Mary and St Michael’s.

Cholera epidemic of 1866

Ironically, it was the energy and selflessness of Fr Ring and his companions that focused attention on the awful overcrowding in East End slums. Tower Hill was particularly vulnerable because it was the landing stage for immigrants and there were little or no medical checks; so epidemics were frequent and serious. The outbreak of cholera in 1866, and what Fr Ring did to cope with its ravages and the threat of starvation during the very harsh winter of 1867 are part of local folklore. He took the lead in forming a Relief Committee, which was able to draw down funding from the Lord Mayor’s Mansion House Fund. John Young was president and treasurer of the committee.

The local Anglicans were advised by the Mansion House Committee to join it rather than start their own separate groups. These committees tended to be ecumenical and helped all in need no matter what age, creed or nationality. This public-spirited action and the priests’ unselfish service to the poor sick broke down any residual prejudice and opposition. Fr Ring’s easy manner and his transparent fair-mindedness won the respect and support of all denominations in those times of emergency.

By the end of the cholera epidemic, the civil authorities had been alerted to conditions in the slums and a slum clearance programme had begun. Within a short time the parish population had fallen by almost 75%. It was this more than anything else that brought the new parish with all its commitments to near penury.

However, mounting financial difficulties did not lead to any reduction in zeal. It was during those trying years that the Holy Family Sisters moved into the parish to give unstinting service in the school, organising social groups, visiting poor people in their homes and providing many vital services. Sodalities were set up to provide not only spiritual formation but also practical education in an effort to compensate for what had been neglected in earlier days.

Overseas fundraising efforts

The crushing burden of debt was a constant worry. Fr Matthew Gaughran OMI, afterwards Bishop Vicar Apostolic of Kimberley, South Africa, went on a fund- raising tour of Argentina to help the parish. His fundraising efforts, however, were short-lived. He was in Buenos Aires when the ill-fated emigrant ship from Ireland, ‘SS Dresden’, docked with 2,000 emigrants. Duped by unscrupulous agents, the new immigrants were abandoned on arrival.

Describing their plight in The Southern Cross, Fr Gaughran wrote, “anything more scandalous could not be imagined. Men, women and children, whose blanched faces told of sickness, hunger and exhaustion after the fatigues of the journey had to sleep as best they might on the flags of the courtyard. Children ran around naked. To say they were treated like cattle would not be true, for the owner of cattle would at least provide them with food and drink, but these poor people were left to live or die unaided by the officials who are paid to look after them”. According to Michael John Geraghty, a Buenos Aires-based journalist and researcher into the ‘Dresden Affair’, “Dublin-born Fr Matthew Gaughran was their only true friend. He discontinued his fundraising, travelled to Napostá and lived for some months with the poor unfortunates attending to their spiritual needs”.

Fr Tim Gubbins was sent to raise funds for English Martyrs in North America, and Fr Crane went for the same purpose to Australia. Notwithstanding those efforts, the parish would have been bankrupt but for the many generous friends whose donations ensured that this church dedicated to the English Martyrs would endure and flourish. Here we can remember with gratitude the generosity of many old English Catholic families who took pride in preserving for posterity the glorious heritage of the past.

The dark cloud of debt began to rise when Fr William Miller OMI (later Provincial, first English Assistant General and finally Bishop Vicar Apostolic of Transvaal, South Africa) became parish priest. He showed considerable business acumen by working out an arrangement that would ensure the parish’s survival. He negotiated a re-financing of the debt through a long-term loan with Alliance Assurance Company, whereby capital and interest were paid off annually over many years. Insurance cover on the property was included. The arrangement came into effect in 1888 and the final payment was not made until 1928.

Working for change

When Fr Cooke returned to the parish in 1877, after serving a second term as Provincial, sodalities were thriving and providing education for poor children and adults through evening classes. He re-established St Catherine’s Protectory for girls and young women. The Protectory grew out of the industrial school for girls previously run by Frances Taylor’s community. It began with the opening of the new school building in 1872. The fact that it quickly disappears from the record would indicate that it almost certainly came to an end within a short time. Many teenage girls were forced to work as street traders to supplement family income. Prostitution offered much greater financial rewards and was a temptation for the more vulnerable.

A report from the London Daily Standard of the time gives some indication of the pernicious influences at work in the neighbourhood: “… to this area come sailors from all parts of the world to spend the hard-earned gains from their long voyages in, for the most part, the most shameful debaucheries… One can scarcely imagine then the depths of vice… that holds sway in this area…”

The Protectory was founded to counteract these influences and the risks to the faith and morals of young people. The programme concentrated on training girls in the crafts of cooking, needlework and general domestic skills. Holy Family Sisters Cecilia Delaney, Gertrude McConaughty and Teresa Rearing took the lead in this work. Lady Londonderry and, to a lesser extent, Lady Herbert of Lea and others supported the project.

Years later, in 1893, Cardinal Vaughan started The Catholic Social Union (CSU) as a diocese-wide movement to mobilise better-off Catholics to run clubs for teenage boys and girls in poor parishes, and, hopefully, start settlements on the model of Toynbee Hall. The Dowager Duchess of Newcastle opened the first of these clubs in Tower Hill, Among those supporting her is this work were Miss French and Miss Claire Fortescue – a descendant of Blessed Adrian Fortescue, one of the English Martyrs. Further clubs soon followed in Mile End. The Duchess started a second settlement at Tower Hill – St Anthony’s – in October 1894. Volunteers continued this immensely valuable work in the parish up to and during World War I. After the War, the landlord sold the building in which it was based and the club was forced to move out of the area.

Catholic troops stationed in the Tower used to attend Mass at English Martyrs. In 1878, shortly after his return to Tower Hill, Fr Robert Cooke was officially appointed RC chaplain of the Tower of London. In April 1880 he was permitted to say Mass inside the Tower, presumably a first since the Reformation (at least with official permission).

Movements and Initiatives

The League of the Cross

Life was difficult and, for those who could afford it, excessive drinking offered a temporary escape from the endless drudgery. The Oblates looked to the League of the Cross, a movement begun by Cardinal Manning to promote temperance, to uplift poor people and save them from the perils of addiction. In time, the Tower Hill branch became one of the largest in the land, and from its ranks emerged the well-known Tower Hill Brass Band.

The C.Y.M.S.

The CYMS (Catholic Young Men’s Society), an association that had its roots in Ireland, was popular with the men of the parish who found in it both a spiritual haven and a social outlet. The Savings Bank established by the Society encouraged a culture of saving and financial prudence, and served the community for more than fifty years.

English-speaking national pilgrimage

By the early 1880s the miracle of Lourdes had seized the public imagination. Tower Hill parish may have been struggling in those years but that did not stop it playing its part in popularising devotion to Our Lady of Lourdes. Fr William Ring organised the first national pilgrimage to Lourdes in 1883. It was also the first mass pilgrimage from England. The idea of national pilgrimages started in France in 1872: it arose from the country’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the idea that the nation ought to do penance and return to God. One of the most successful of the French pilgrimages that year was to Lourdes. The Oblates from Marseilles were involved. Prior to 1883, it had not been possible to get together enough English Catholics to form a credible national pilgrimage. And without sufficient numbers it was impossible to negotiate affordable fares. The project did not get off the ground until Fr Ring and a Tower Hill parishioner had the idea of enrolling people as pilgrimage associates, so that a relatively small number of actual pilgrims could represent thousands of others. In the end, quite a large number travelled as a joint pilgrimage from England and Ireland. On May 13th of that year, 300 pilgrims attended Mass at the Shrine of Our Lady of Graces and set out for Lourdes, bringing with them 100, 000 petitions to deposit at the Grotto of Massabieille.

The Guild of Our Lady of Ransom

In 1887, Fr Philip Fletcher formed The Guild of Our Lady of Ransom with the help of co-founder, Fr James O’Reilly OMI, Parish Priest at English Martyrs. The Guild held monthly meetings in Tower Hill Presbytery and met for devotions before Our Lady’s Shrine. Two types of procession were held under the auspices of the Guild: pilgrimages to the Tower in honour of the English Martyrs, and processions to honour Our Lady.

In 1890, a crowd of some 2,000 people simply walked from English Martyrs Church to the Tower. Although some were allowed enter the Tower, there is no evidence this was a formal pilgrimage. Formal processions in honour of Our Lady, with banners etc, began at Tower Hill in 1892, and were soon taking place in many London parishes.

In 1893, a more formal pilgrimage through the streets to venerate local places hallowed to the memory of the Martyrs almost certainly marked a coming of age for the Guild. The emotional significance of this Catholic procession through the streets of London is difficult for us to reconstruct.

The Daily Graphic of the time reported: “The gates of the Tower were closed at 4.30 pm and shortly afterwards, little groups of pilgrims began to gather round the square on the grass where the scaffold once stood; lilies and lilac and irises in wreaths and bunches bloomed vividly against the grey granite stone. Some children loitering in the garden came up to watch outside the garden railings. The proletariat of Tower Hill, rather down at heel, looked on at the curious ceremony, with feelings that hesitated between amusement and disapproval. The ceremony was brief. A few short addresses by Fr Dalton and Fr Fletcher set out reasons why the saints and martyrs, Blessed John Fisher and Blessed Thomas More, should be honoured in their deaths as in their lives. There followed a space for silent prayer… When the prayers were over, many pilgrims bent down and kissed the ground… Several priests were present in this little pilgrimage when, for the first time in 300 years, public respect was shown for the spot on which the best blood of England was shed.”

Catholic Seaman’s Club

In 1893, The Catholic Seaman’s Club, which along with other early efforts to support Catholic seamen would later develop into the Apostleship of the Sea, was opened at No. 18 Wellclose Square; in 1897 it moved to No. 16 as a Seamen’s Home. It was still a Club, but with cubicles where men could stay overnight. The Club was under the aegis of the Catholic Truth Society. In fact it was the Oblates and parishioners involved in the Guild of Ransom and the League of the Cross who ran it. The parish was helped in this work by contributions from key friends such as, Lady Amabel Kerr, the Duchess of Newcastle, Hon Mrs Fraser, Lady Herbert, Messrs, de Trafford, Oates, Drummond, Blenzberg, Count de Torre Diaz, a City businessman named Charles Raikes and many more.

Twentieth Century Begins

Urban renewal threatens parish school

When the time came to redevelop London’s East End, restrictions were expected, but plans that would lead to the closure of the parish school were another matter. When Fr O’Carroll became parish priest in 1896, he was faced with this problem. The extensions to Fenchurch Street Station and its approaches encroached on the parish’s buildings and services. The Department of Education judged the noise from the railway excessive, and the reduced light in the classrooms no longer adequate. The school building was no longer suitable, so an alternative site would have to be found for a school.

It was a tall order. Even if a site could be found, it would be impossible to pay for it. It was the resourceful Fr Ring who came to the rescue with an alternative scheme. He was passing through London when he heard the annoying news that the fine school he had built twenty-five years before was to be pulled down. He advised protest, negotiation and arbitration. He rallied influential people to the cause, including Cardinal Vaughan, the Duke of Norfolk and all the friends of Tower Hill. A plan for some additions to the school and alterations to the classrooms was put forward as a solution to the impasse. The Education Department approved the scheme, which required the removal of the sacristy. The school was saved and, at £4,500, the cost was bearable.

Martyrs’ canonisation

Towards the end of the 1920s it became evident that the canonisation of martyrs, John Fisher and Thomas More could not be far off. The parish community felt with new urgency the need to build a permanent shrine to the English Martyrs. The shrine, which is our High Altar, was erected in 1930. Five years later, on Sunday, 30 June 1935, our two best-known martyrs were canonised. The Guild of Ransom arranged a day of great celebration that was a public triumph. A long procession wound its way from Lincoln’s Inn Fields to the Scaffold Site on Tower Hill where two beautiful banners of the new saints were blessed and handed over to the custody of our church, to be used in the annual Martyrs’ Procession. The greatly augmented procession moved from the Scaffold Site on to Prescot Street, where Cardinal Hinsley led Benediction in the open air from the steps of the convent.

War clouds gathering

Tower Hill seemed so peaceful. The Tower was a prominent tourist attraction drawing a constant stream of visitors. It was an ideal place for public preaching and a marketplace for every known “ism”. As the 1930s moved on, the horizon grew more gloomy. The dogs of war were let loose once again and the East End was forced to endure unparalleled danger and suffering. London’s dockland became a prime target for aerial bombardment, and our people had to endure dreadful times. Local people would make their way at night to the scant comfort of the public air-raid shelter or the platform of an Underground station, there to snatch a few hours of troubled sleep. Worse still was the constant danger of death raining from the sky during the “blitz”. The morale of the people was little short of miraculous as they withstood the trials of those days. On 29 December 1940, a 500-kilo bomb hit the church. Fortunately it did not explode; it tore its way through the roof, made a deep gash in the side wall and lodged in the floor, completely demolishing the pulpit. The unexploded bomb was not removed until February 5th of the following year.

In the meantime, until temporary repairs could be carried out, Mass was celebrated at Conches’ shelter in the Highway, generously lent to our parish community by that firm. The Blessed Sacrament was reserved at 34, Wellclose Square. The presbytery, too, was badly damaged and the Fathers had to move out to lodgings.

Temporary repairs were carried out and the church was in use again on Passion Sunday, 30 March 1941. When an appeal went out for helpers to clean the church for the Easter ceremonies, an army of women with buckets and mops made a vigorous attack on three months of wartime grime. Our neighbours fared much worse.

The German church was destroyed; SS Mary and Michael’s on Commercial Road was extensively damaged and the bomb that killed the clergy there also demolished Dockland across the river.

Restoration work on the church was not completed until Fr Robert Nolan’s time as Parish Priest. This work proved expensive, but war damage was assessed on 1939 standards and did not take increased costs into account. Money had to be found urgently, but how? The answer came in the form of the Parish Football Pools and was a tremendous success. Credit must go to the instigator, Fr Willie O’Brien and his many willing helpers. Thanks to their efforts, the parish survived and prospered in difficult times. The church was repaired and decorated, and later, in Fr Fitzsimons’ time as parish priest, it was further enhanced and beautified.

Time to celebrate 100 years

Civic and Church dignitaries joined in celebrations to mark the centenary of English Martyrs Parish in 1965. The attendance included the Apostolic Delegate, Archbishop Cardinale, the Irish Ambassador, Mr. Molloy, and Cardinal Heenan, who praised the work done by the Oblate Fathers and the Holy Family Sisters in providing education for adults and children, even before the days of compulsory education.

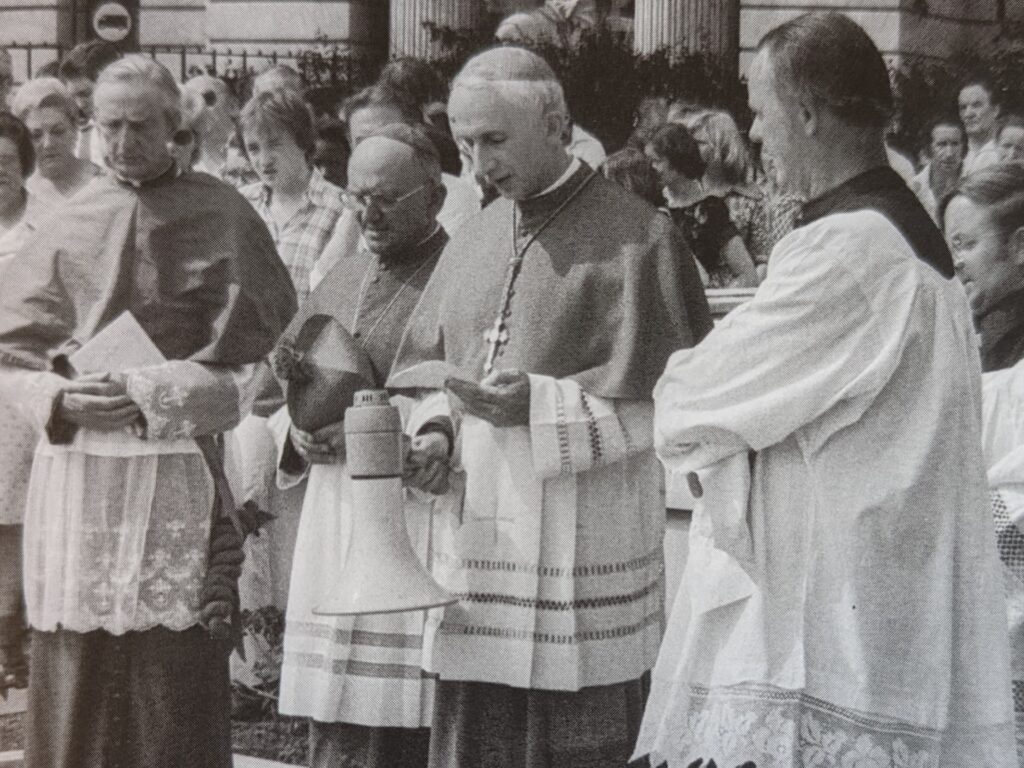

Fr Jim O’Boyle managed to acquire a site in St Mark Street for a new school during the centenary year, but the school was not completed until 1970, when Fr Paschal Dillon was parish priest. Cardinal Heenan came to bless and open the school on 20 June 1970, exactly one hundred years to the day since Princess Marguerite of Orleans laid the foundation stone of the old school. When the old school was vacated, work began on converting it into a comfortable community centre. Cardinal Basil Hume, then newly appointed Archbishop of Westminister, paid his first official visit to the East End on Sunday, 27 June 1976. Accompanied by Bishop Guazzelli, he led celebrations to mark the centenary of our church. Among the guests were the Duke of Norfolk, whose ancestor was present at the opening of the church, and Councillor D. Kelly and Mrs. Kelly, Mayor and Mayoress of Tower Hamlets.

Adapting to change

Sadly, after a hundred and fifteen years of faithful service to the people of English Martyrs Parish, the Holy Family Sisters left us in 1985 and their convent was demolished. The old presbytery at 26, Prescot Street was also demolished and with it went the sacristy. Fr Paddy Coady shortened the church by placing a glass partition at the rear, thus giving us a decent porch and a new sacristy.

In 1991, Fr Hartford removed the sanctuary extension and returned the altar to the original sanctuary. He also had the church repainted and carpeted, giving it an air of serenity and peace, which is enjoyed, not only by our parishioners, but by the large number of City commuters, who regularly attend the one o’clock Mass during their lunch hour.

Demographic changes continue to exert their influence on our parish community. The City is constantly extending, bringing further office blocks and hotels, but the dwindling congregations of the last few years have been reinvigorated. Today, our school is once again thriving, and the Martyrs, who were prepared to lay down their lives for their Faith, must rejoice to see so many come here to worship their God.

As in the past, the East End of London welcomes people from all over the world who come here to live and work, and increasingly just to visit. According to The Tablet, when the foundation stone of English Martyrs church was laid in 1873, Catholics and Protestants, Jews and Muslims all joined in hanging out flags and banners to decorate the street. In the late 1890s when one of the priests was interviewed for the ‘Charles Booth Survey’ he stressed their excellent relations with their Jewish neighbours. At that time the population was for the most part nominally Protestant, but with large numbers of Irish and German Catholics, a sizeable Jewish community, and a tiny Muslim community; later the area became predominantly Jewish; today it is predominantly Muslim.

In Twenty-first Century multi-cultural Britain, we can recall with gratitude that our parish community is heir to a tradition of respect, tolerance and fair- mindedness that goes back to the foundation of Tower Hill mission.